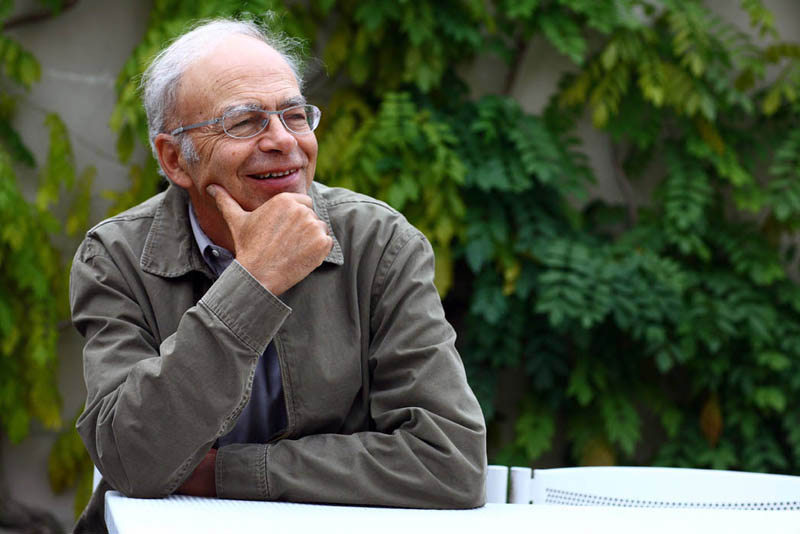

Interview: Peter Singer

I first heard of Peter Singer in 1989, when I was a teenager and I got the album We're Not In This Alone by the band Youth of Today. At that time, the record was so cool to me on so many levels: the music, the lyrics, the graphic design, the imagery, the cultural references… And the lyric sheet had something that I'd never seen printed with a record before: a reading list. That simple thing took that record to another level for me. While the lyrics on the record had a prescriptive slant, the reading list raised it to the purely philosophical. And that completely called out to me as a teenage kid.

Among a list of titles that included things as wide-ranging as Vedic religious texts was Animal Liberation by Peter Singer, an Oxford-trained academic who would emerge as one of the leading (and more controversial) philosophers of the late 20th century. It wasn't long after I finished reading his book when I began to follow a vegetarian diet and be more thoughtful about a lot of other things in my life that up to that point I had taken for granted.

I spoke with Dr. Singer one afternoon years later in his office at Princeton University. We talked about his academic career, how he got interested in animal rights, the background behind writing Animal Liberation and some of the arguments for following a vegetarian diet. The following is a transcript of that conversaion.

This interview was recorded on the afternoon of November 20, 2000 in Dr. Singer's office in Princeton, NJ.

I'd like to start out by talking about your background and life. Could you give some information about your academic experience, and how that led to writing Animal Liberation? How did this course in your life begin?

It's a fairly straightforward academic career, I guess. I was educated in Melbourne, at the University of Melbourne, and then did graduate work at Oxford…and then I had my first teaching job at a university at Oxford, after I graduated…came back to Australia, because I was already married when I went to do the graduate work at Oxford…and my wife and I both had parents living in Melbourne and we wanted to be near them as we…by the time we both came back we already had our first child…I actually didn't come straight back…I had a year at New York University.

It was at Oxford that I first became aware of the animal issue. I just happened to get talking to a fellow graduate student…a Canadian…and we went back to his college to have lunch…and when the lunch was…there was, like, kind of a choice of dishes for lunch…a buffet…and there was some spaghetti with sort of, like, a brownish sauce on it, and he asked if the sauce had meat in it…and he was told that it did. He took a salad instead. So, then I asked him, you know, “Why didn't you want the meat?”…because at that stage, vegetarians were fairly unusual…and he talked about, you know, saying that he didn't think that humans ought to treat animals the way that they do treat animals that end up being turned into meat. So, I talked to him a bit more about it and it was kind of unusual, because most of the vegetarians that you'd heard of were either vegetarians for their health, or they were kind of vegetarians who were pacifists, and didn't believe in killing and thought that it was always wrong to kill. And I was neither. I knew…you know, both of those seemed to me to be not things that I would regard as sound reasons…but this was different because in a way he was relating it to the suffering we inflict on animals more than to the simple fact that they're killed. And so I inquired further, and talked to a couple of other friends of his who were also vegetarians, and started reading a little bit about how animals were treated.

There wasn't very much to read at that stage, but there was one book by a woman called Ruth Harrison called Animal Machines, which described just newly developing factory farming. And I did find that fairly appalling, and I started to think about what is it that would justify us in treating animals the way that we do. First, you know, I thought, Well…there must be some important difference between humans and animals that justifies us in doing this to them when we wouldn't be justified in doing it to other humans. But, the more I looked into what other philosophers had said about this, the weaker it seemed.

Philosophers…you know, great philosophers of the past…were either evasive, or they ignored obvious questions like…Kant talks about humans being an end in themselves and animals being mere means…and he seems to base that on the idea that humans are rational and autonomous. But, of course, it's obvious that not all humans are rational and autonomous…babies are not and humans with severe intellectual disabilities are not…and some animals are much more rational and autonomous than those humans. But neither Kant nor his more modern followers ever took up that question and asked themselves, “Well, does this mean that it would be okay to fatten up babies or intellectually disabled humans and eat them?” Or, “Does it mean that it's wrong to eat animals if they actually are rational?” Those questions were just never asked, and so I started, eventually, to see, well…something's gone wrong here…there's a pattern of evasion…of avoidance of the issue. There's, like, an assumption that somehow, you know, this must be right…but no one really bothers to justify it properly.

Like there's some logical error.

Right. And eventually I came to think, Well, it's not that there's some argument that I haven't yet discovered…it's that something really is…there is something wrong going on here, which nevertheless is in the human's interests and so it generally doesn't get challenged. It just gets accepted.

So…anyway, that was kind of, like, an interruption in what I was saying about the academic career. So, I went to New York from Oxford and I…well, let me go back a bit further…before I left Oxford, I had written a review for the New York Review of Books of a book produced by two of these of this group of Canadian students that I met. They'd edited a book called Animals, Men and Morals, which contained a collection of essays about the issue of the treatment of animals…edited by Roselyn and Stanley Godilevich and John Harris…and, it was published in England, but it really did not catch any attention at all. It was not reviewed. It was basically just ignored, and…they were very disappointed because they did think that they had something very new to say. And so I thought that maybe the place that would publish something of this would be the New York Review of Books, which was then the leading sort of intellectual marketplace of ideas. So…when that book was ready to be published in the United States, I wrote to the New York Review and outlined why I thought this was an important issue and the kind of review I thought I'd like to write. And they said, “Go ahead.”

So, that was the first piece I published on the animals issue, and that came out in 1973 in the New York Review of Books and attracted quite a strong response and a letter from a publisher suggesting that I turn it into a book. So, when I then went to New York for a one-year visiting position at New York University, I started working on turning it into a book. And I had that pretty much done by the time that I left to go back to Australia…which was in Christmas of 1974.

That book was Animal Liberation.

Yes…that was Animal Liberation.

It turned out to be an important book.

Well…I think so. I mean, it certainly had an influence on the development of what became the animal rights movement. There really wasn't any such movement at the time. I mean, there were the traditional animal welfare organizations…the SPCAs, the Humane Societies…but they were very much focused on issues about dogs and cats and horses and so on, and really took a very very soft line on any kind of major commercial use of animals. That was not what they were opposing. And there were some anti-vivisectionist groups, but they were pretty marginal. So, I think what Animal Liberation did was to show to a lot of people that their concern for animals wasn't just a matter of sentiment or emotion. For animal lovers, it wasn't just a matter of thinking that animals are cute and cuddly and shouldn't be used in these ways. It was actually a moral issue that was comparable to the other great moral issues of the time…things like the black liberation movement and the women's liberation movement. And there were a number of other movements to work for equality for large sections of human beings. And I called my book Animal Liberation in order to make a parallel with those movements and to suggest that there was a need for a similar movement in relation to our attitudes toward non-human animals. And I guess, over the years, a lot of people have come to me and told me that the book has had a big impact on them…has led them to become a vegetarian, helped them to get involved in the animal movement…generally changed their lives.

Well, then I went back to Australia and taught philosophy at a couple of universities in Melbourne…wrote Practical Ethics in 1978…which is a book that deals with a wide range of practical issues, not just the animal issue but includes the animal issue…

I've read that book.

Right…so you know that it talks about things like our obligations to the poorest people, it talks about issues relating to the sanctity of life… And that's also been quite a successful book. I mean, more aimed, I guess, at the college student level…

And then, a few years later, I helped to found something called the Center for Human Bioethics at Monash University, which was a center looking at ethical issues in medicine and the biological sciences. I've written a number of books since in that field about artificial reproductive technology, about the treatment of disabled newborns, about embryo experimentation…other issues in the sanctity of life area…as well as still doing some things in connection with animals, like co-editing a book called The Great Ape Project, about the treatment of gorillas, chimpanzees and bonobos…making the claim that we ought to recognize them as having certain basic rights. And…you know…during that period I had three children and I've sort of grown up and become independent, and a year or so ago…well, let's see…a couple of years ago I received an invitation to allow myself to be considered for this chair at Princeton…and when that was offered, I decided that would be an interesting challenge…to come back to America and take part in the very lively debate that goes on here about these issues.

So, relating to vegetarianism, what kind of personal arguments do you give for your opinion on that issue? How would you…

I wouldn't call them personal arguments, because I think they're just general ethical arguments…

Okay…what kind of arguments would you give? How would you argue for vegetarianism?

For people living in societies like the United States, where there is an abundance of vegetarian food, where there's no question of having to go short on food or short of adequate nourishment by becoming a vegetarian, I would argue for it simply on the basis that the desire for that particular kind of taste—which is basically what meat eating is, given that choice of food I just mentioned—the desire to have one particular kind of nourishing and sustaining dish rather than another, on grounds of taste, could not possibly be enough to justify inflicting great suffering on nonhuman animals. But if you look at the way that animals are raised in modern agribusiness and intensive farming, or "factory farming", it is clear that that is exactly what happens: the well being of the animals, their interest in living even a minimal, decent life, is completely overridden by the competitive market forces that, in the absence of any regulation, have forced farmers to produce their meat products or their eggs, or whatever it might be, as cheaply as they possibly can. So, if it becomes cheaper to bring all the animals indoors, to confine them in narrow pens so that they can't walk around, or to keep hens in cages where they can't even stretch their wings, then that's exactly what farmers will do. And my argument is that there is no justification for inflicting that kind of suffering on animals that could possibly come from situations where it's not a life or death matter to actually have that meat. And it's clearly not a life or death matter. As I was saying, we have a great range of alternatives. And, in fact, it's even more efficient. It's ecologically more sound to eat vegetable and plant products directly rather than to feed the plants to animals and eat the animal products as a sort of second-hand way of getting what the earth produces.

For someone who was skeptical about your position, they might ask, Why should anyone care? Why care about what animals feel?

Well, I mean…someone can be skeptical about ethics in general. You can say, "why care about what people in Kosovo feel," for example. "America Shouldn't have gone in. Sure, the people were being killed, but why should we care about that?" Why should we care about what happened in Rwanda when 800,000 people were slaughtered? For that matter, you know…why should I care about someone who I see on the street, who falls over and is obviously hurt?

You can be a skeptic about caring about anything or anyone, I guess, other than yourself. And that kind of skepticism is hard to answer. I mean, most people wouldn't want to be that sort of person who doesn't care about anyone else. Most of us wouldn't like such a person. But to actually say, "well, is that person irrational?" is a bit difficult. It's hard to imagine that they actually enjoy their life or live a satisfactory life if they're so purely self-centered. But if they do, it's hard to refute.

But once someone starts saying, “Well, yes…you know, I do care about people in Rwanda” or “I do care about people in Kosovo,” then I think maybe you can say, “Well, great. So do I. But why do you limit your caring at the boundaries of our species? Why do you care only about humans, and not about members of any other species?” And it's at that point that I think the argument becomes much tighter, because someone who does care about humans, and particularly, for example, someone who objects to racists, who says “I care about humans but only if they're members of my own race”…such a person is, I think, stopping at a arbitrary point if they say, “I care about all members of my species but I won't care about all members of other species”…because there's no reason why species should be a morally relevant boundary. And, if we reject the idea of race as a morally relevant boundary and say, “Well, it's arbitrary for you to say that you're going to care for people of your race but not of some other race”…then I think the same thing goes for species.

Some of your arguments have attracted a lot of controversy because some people would say that they devalue human life. And, in regards to some of the arguments that you use to justify animal rights, critics have said that you do that at the expense of the value of human life. How do you answer that?

Well, I think that once you realize that species is not in itself a morally relevant boundary, there are then effectively three possibilities which you exhaust as far as things like the value of life is concerned. You could say, “Okay, species is not a relevant boundary, so therefore we should give all nonhuman animals—or, let's say all sentient creatures—the same right to life that we now give to humans.” That's one possibility. The second possibility is that you could say, “Species is not a relevant boundary, so we should now extend to all humans the same views about the value of life that we currently hold for nonhuman animals.” And the third possibility is obviously some kind of middle position, that you say, “Well, rather than just treat all animals as we now treat humans or treat all humans as we now treat animals, we'll find some middle ground where we'll treat some humans and animals in a certain way and perhaps others in another way.” And of those three positions, I think the third is really the only defensible one. I think no one would want to go to the second, really. No one would want to say, “Well, we're going to treat humans as we now treat animals,” so that if someone wants to, you know, fatten a human and kill and eat that human, then that becomes fine.

Some people might initially say we should go with the first point that I mentioned—that is, that we should extend the same protection of life to animals that we now extend to humans. But I think there are some serious objections to that, because the protection that we give to human life is not one based on consequences. So, for example, it would mean that if you had a sick animal that you knew was going to die and was in a lot of pain and stress, you couldn't take it to the vet and have it put out of its misery. You couldn't have it put down, because we don't do that to humans. It's not lawful to do it. So, I don't think that's a satisfactory outcome, either.

So, that's why I end up with a middle position—that is, you make some changes that in some ways bring humans and animals closer together. And inevitably, if you do that, you are going to down value the lives of some humans—not necessarily all of them, because I think what you can do is you can look at certain characteristics, not species…but I think characteristics that might really matter morally, and one of them might be having certain rational capacities or, as I've suggested in Practical Ethics, having the ability to consider yourself as an independent living thing with a past and a future. And that, I think, is something that makes it worse to kill a being, because then you're cutting off that being's desires for the future in a way that you couldn't do otherwise if it didn't have those desires.

So, the view that I come down with is, where you have beings like that who are capable of seeing that they have a past and a future—and I use the term “person” to describe such a being, which is an ancient philosophical usage of it, following John Locke, who called a person a “rational and self conscious being.” So, once you have a “person”, then I would say, then, yes, you should give life roughly the same protection that we now give to…not exactly but roughly…

But, if you're not a “person”, then you might still be a being in respect to whom it matters what you do morally…that is, you might be a moral subject because you might be able to feel pain. But just on the question of killing, I would then say it's not wrong to kill such a being, other things being equal, because that being doesn't have the sense of loss that a being has if it sees itself as existing in another time. Perhaps I should have said there that it's not so seriously wrong to kill that being…I don't want to say it may not be wrong at all…it could be because there is the loss of the happy life, the pleasant life of the being…and if there's no compensation for that, then that would be wrong…but maybe in some ways that could be made up for and then that would not be wrong on some level.

At the beginning of our conversation, you mentioned a couple of things that strongly influenced you…one was your friend that you went to lunch with. Obviously he had a strong effect on you.

Well, he and the other Canadians, because what actually happened was that, you know, as I said, we had that lunch, and I started talking, and he then said “Well, if you're interested, then just come and talk with this other Canadian couple.”

Actually, he had met them—he and his wife…Richard and Mary Fisher—had met them on a boat coming over from Canada, and they became vegetarians after meeting them. So, then, basically, they were four of them—the other two that I mentioned, and Roselyn and Stanley Godlevich. It was the four of them, really, that had an influence on me. And of that four, I think probably Roselyn Godlevich was the one who…well, she was not the first one that I met, but she was the one who I spent most of the time discussing it with, and who seemed to me to be the tightest and clearest in her argumentation.

What other things or people strongly affected who you are and who you've become over the course of you life?

Well, obviously, anyone's parents have an influence on them, and I think from my mother I got a pretty good skeptical intelligence. She was a medical practitioner. She was always sharp in conversation and had a good mind, I think, which she used critically. She was not accepting of religious beliefs or things like that, which she thought could not be justified.

My father, I think, also, you know, liked to argue…and I think I got a bit of that from him. But he—more than my mother, I think he had a warm sense of compassion for animals…more than my mother did. And although he was not at all a vegetarian and was never active in protecting animals, he…for example, I remember we used to go out on the beaches for walks, and we would see people fishing and they would have caught fish and they would just leave the fish flapping in a basket beside them while they sat on the beach. And he would say to me, you know, “I can't see how anyone can think it's fun to sit there all afternoon just killing fish and watching them die slowly beside you.” And I think that's sort of why, I think, he made an impression on me.

Other than that, my wife certainly has been an influence on me, because we got married fairly young, when I was 22, and she's a person with a strong moral sense. And I think when we started talking about this issue about animals, and also, separately, when we started talking about questions of world hunger and what we could do, you know, she was always the one who said, “Well, look, you know, you think, if this is right, then we ought to do it. We shouldn't just sort of say it's right, as if it made no difference. We ought to do something about it.” So, I think, in a sense, that once I was intellectually convinced about the animal issue, we decided together to become vegetarians, and I think that was important. Then we decided together to give some of our income to agencies helping the world's poorest. So, I think all of those things were…well, she was a big influence.

And finally, philosophically, I must mention my teacher at Oxford, Professor Aaron Hare, who I think is one of the more important moral philosophers of the 20th century. He taught me about ethics and moral argumentation.

How about your day-to-day choices? What comes into play there?

Well, obviously I'm concerned about questions like having a lifestyle that minimizes the exploitation of animals. I say “minimizes” rather than “avoids” because I don't think you can ever completely avoid it. You could go crazy trying to worry about whether there's some gelatin in a film that you've used in a camera or whatever else it might be. So, I'm not fanatical about it, but generally I try and avoid purchasing animal products and that affects the clothing I wear, the shoes I wear, and so on.

In terms of things like getting around, I've sort of…since we've come to America, we've managed to live without a car, which I think is both convenient and ecologically desirable. But when we were living in Australia, it really wasn't possible, because there just wasn't the form of public transport that there is around the New York region. But, in general, I think you should be aware of the ecological impact of what you're doing. But, again, there are different choices as to how far you push that.

And, in general, I think knowing as we do how incredibly privileged we are, and how there's more than a billion people in the world living on a dollar a day, I really don't like…sort of…luxury or ostentatious spending. I think it shows a sort of lack of appreciation of the situation of other people…and the fact that what you're spending could be helping other people and making a difference in other ways.

It seems that those approaches have worked well for you.

Well, I'd have to say so. I've been incredibly lucky, because I've been able to do these things and still live a comfortable life and, basically, I have work that I really like doing. I think that's the greatest good fortune you can have in life—to really work because you like the work that you're doing and not just because you need to earn the money somehow. That's the wonderful thing about universities like this is that they give the opportunity to do the sorts of things that I like to do. And, I guess, I just honestly think that it's very fulfilling to know that, in fact, you have made a difference to the world…a better direction, whether for animals or humans.

Links

- General Biography (Wikipedia)

- Peter Singer's personal webpage (Princeton University)

- Television interview transcript (Australian Broadcasting Corporation, May 22, 2006)

- Animal Liberation at 30 by Peter Singer (The New York Review of Books, May 15, 2003)

- What Should A Billionare Give? by Peter Singer (The New York Times Magazine, December 17, 2006)

- The Singer Solution To World Poverty by Peter Singer (The New York Times, September 15, 2003)

- Links to other online articles by Peter Singer (Utilitarian.net)

- Buy Animal Liberation and other works by Peter Singer (Powell's Books)

- Buy Animal Liberation and other works by Peter Singer (Amazon)

- Oxfam International